The first ever Tipping Point: Critical Sustainabilities unconference took place as planned on 30.9.2025 with around 100 participants visiting the event during the morning, afternoon and/or afterparty.

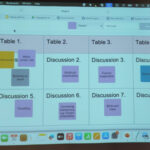

Having had the registration open just 2 days, we got 120 registrations to a space with a limit of 100. We did not expect for the news to travel that fast nor did we expect to get 30+ interested participants to submit their presentation topics. For an unconference, we felt that every submission ought to be accepted so we replanned the day and gave every presenter in the morning on stage to afternoon in the roundtables an equal 5-minute slot.

From the audience activations throughout the day we know that we had; the academy, public sector, NGO/NPO, businesses, artists and journalists, activists, independent doers, entrepreneurs and freelancers all represented -- representing more than 30 different affiliations.

We had such themes as; critical approach (philosophy [of science]); activism and social movements; sustainability transformations; future developments (the risks in); plurality in sustainability; critical status of climate change; critical (to) economics; new methods and tools; solutionism (in mainstream sustainability); critical planning and governance; collaborations between fields and sectors and global and local injustices at the foci of the presentations.

When asked what was the participants' approaches to the "critical" in critical sustainability, such comments were posted as; "bottom up instead of the waterfall"; and "participation" to "thinking of power and capital" and "frustration to what's happening in the world".

In the spirit of the event, the final words were given by a participant, whom spoke of storylines and suggested that rather than close-ended, we should take this to be an open ending to this event: this is from where it lives on. Another participant suggested listening to a song and so did the Tipping Point finally close, participants dancing to Kool and the Gang's Celebration, cleaning up the space together, before moving to the afterparty with more music and live poetry.

Thus it seems quite clear to us, that something like this; not just the event but the theme, these conversations, these thoughts and questions, these approaches in academia and outside and especially between, are much needed.

Stay tuned to see what happens next--we will do so too!

Thank you to the Tipping Point speakers, artists, and facilitators:

Pasi Takkinen, TUNI

Rosa Rantanen, INAR/UH

Linda Karjalainen, SYKE

Hanna Granroth-Wilding, Scientist Rebellion/UH

Martin Fougère, Hanken

Anni Leppänen, Falay Transition Design collective

Niina Ollanketo, Yhteisöllinen Oulun seutu ry

Hannu Häkkinen, Global Sumud Flotilla & Random Doctors

Benjamin Pitkänen, Viral Vegans

Michael Lettenmeier, UH

Mikael Nurminen, TUNI

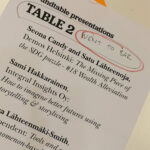

Seona Candy, Demos Helsinki

Satu Lähteenoja, Demos Helsinki

Sami Hakkarainen, Integral Insights Oy

Kaisa Lähteenmäki-Smith, independent

Lauri Palsa, JYU

Ronja Tammenpää, Aalto

Laura Wiman, VTT/UH

Sakari Mesimäki, University of Cambridge

Riina Bhatia, UH/VTT

Heikki Hackman, Independent/Tribe of Ephic Trackers

Corinna Casi, UH

Tatu Marttila, Aalto

Juni Sinkkonen, UEF & Tunne ry

Rami Ratvio, UH

Ayonghe Akonwi, UH

Sonja Holopainen, UH

Sini Holopainen, UH

Janne Salovaara, UH

Eetu Haverinen, Kuohu & Kaisla

Kasper Salonen, spoken word poet

Teemu Loikkanen, University of Lapland, Puistokatu 4

Dj LauraPop

Dj Kolektiv

And all other participants and colleagues as co-creators of the event!